Verb Thinking and Neo-Enlightenment

- Date: March 26, 2025

- Location: Yannan Garden No. 54, Peking University

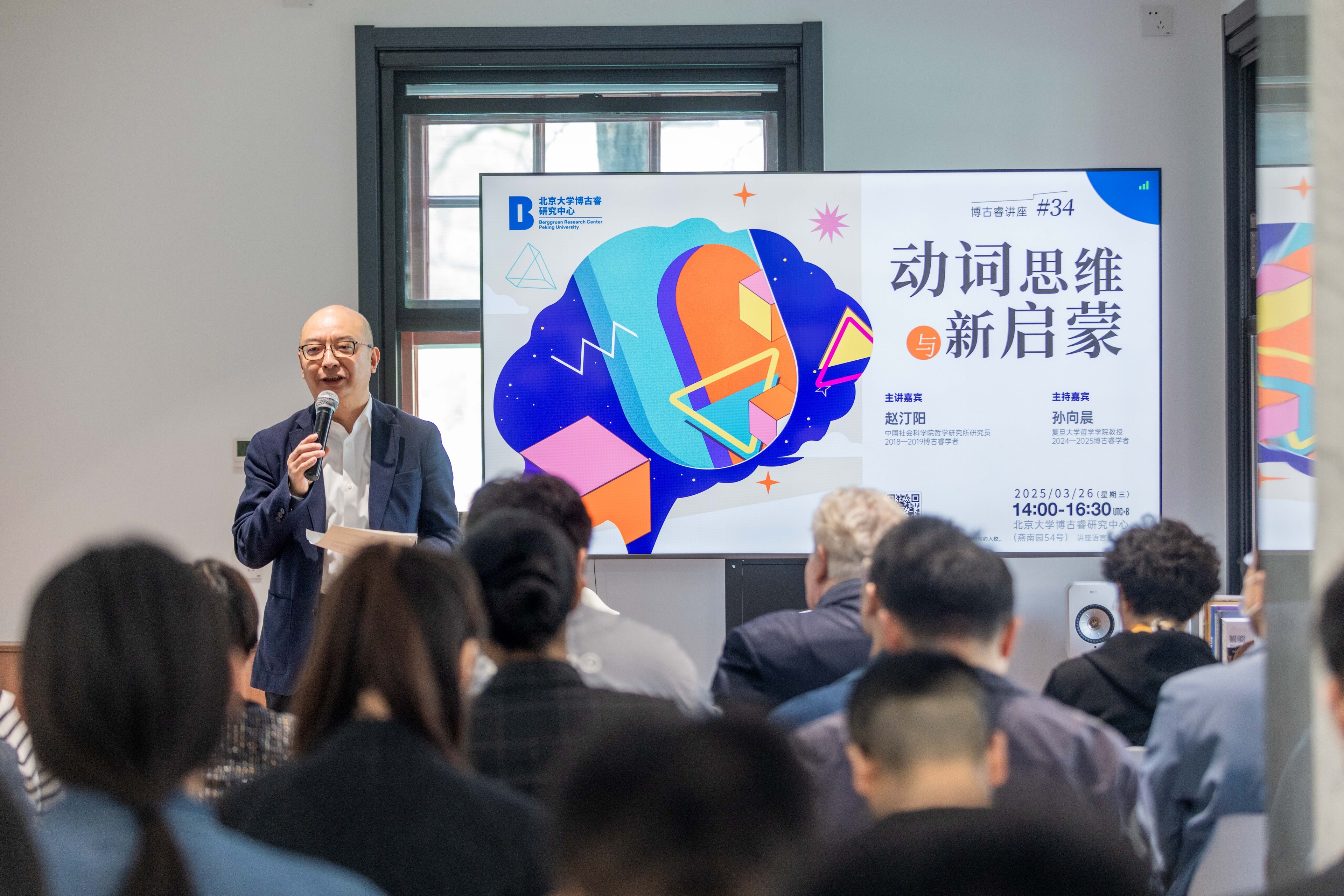

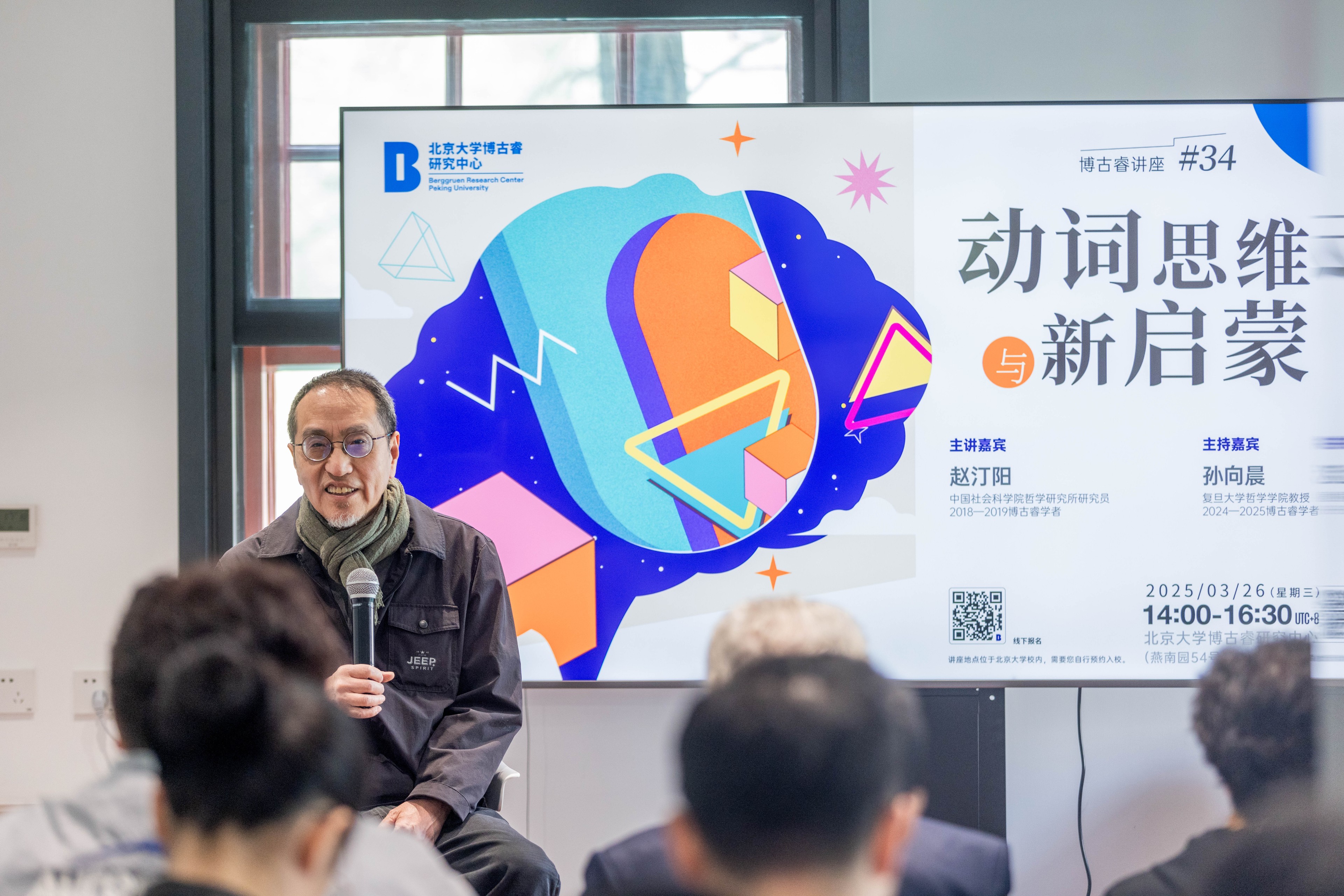

On the afternoon of March 26, 2025, the 34th Berggruen Seminar Series titled "Verb Thinking and Neo-Enlighenment" was held at Berggruen Institute China’s new office No. 54, Yannan Garden, Peking University. This lecture was presented by Professor Zhao Tingyang, a researcher at the Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, and a Berggruen Fellow from 2018 to 2019. It was hosted by Professor Sun Xiangchen from the School of Philosophy, Fudan University, who is also a Berggruen Fellow from 2024 to 2025.

Professor Zhao Tingyang pointed out that under the impact of artificial intelligence and technological waves, the traditional enlightenment's "nominal thinking" has become inadequate to cope with the complexity and volatility of the modern world. Nominal thinking, which centers on classification and definition and emphasizes the static attributes of things, has contributed to the development of human civilization. However, this mode of thinking is incapable of effectively explaining the dynamic, uncertain phenomena that are increasingly emerging. Perhaps we urgently need a new enlightenment: establishing verb thinking beyond nominal thinking to understand the dynamic existence, unpredictable emergence, and creative singularities of civilization that nominal thinking fails to explain.

The Formation of Nominal Thinking: Path Dependency of Human Cognition

As early as 1998, Professor Zhao Tingyang introduced the concept of "verb thinking" in his book One or All Problems. In recent years, as he has delved deeper into this topic, he has found that since artificial intelligence inherits "nominal thinking," many complex problems remain unresolved at their root. Although "complex science" is dedicated to studying phenomena that reductionism and probability theory cannot explain, its methodological progress over the past three decades has still been constrained by nominal thinking, making it difficult to meet the challenges posed by complex knowledge. This has prompted us to further reflect on whether our language structure limits our way of thinking.

Professor Zhao Tingyang observed that human languages, without exception, are noun-centric, with other parts of speech playing only auxiliary grammatical roles around nouns. This noun-focused intentional feature guides our thoughts primarily to two major questions:

The first is "What is what?" This is the fundamental theme of all knowledge, involving the construction of concepts, definitions, and even meanings. Because knowledge is largely expressed as effective definitions and classifications of concepts.

The second is "What explains what? What causes what?" This touches on the exploration of causal relationships, which is also the foundation of natural science. The exploration of causal relationships is usually achieved through the connections and comparisons between things in the nominal system.

These two core questions form the framework of nominal thinking. Nouns constitute the common topics of our life, thought, and knowledge, around which we weave the "stories" of our thoughts. From Aristotle's "genus plus specific difference" taxonomy to modern mathematical logic's category theory and causal science, and even the regulations and identity systems in humanities and social sciences, all are knowledge structures built on the order of nouns. Strictly speaking, except for proper nouns, all nouns are metaphysical. The entirety of knowledge is equivalent to an encyclopedia of nouns, with a priori order supporting our language and thinking activities.

If we trace back to the initial state of language, how did the noun-centric cognitive path form? Professor Zhao Tingyang believes that from a simple signaling system to a complex spiritual world, language development experienced a "genesis." The historical singularity that constituted this was the invention of "negation." It brought about a series of important cognitive advancements.

Firstly, negation introduced the concept of possibility. Before the emergence of negation, language only expressed actuality, and the appearance of negation led to the emergence of infinitely many possible worlds in ontology. Secondly, negation endowed language with the ability to self-explain. Language no longer merely described things directly but could explain itself. At the same time, negation also promoted the self-reflective ability of consciousness. Thirdly, negation marked the birth of the future. In nature, time is just a continuous process. We can use negation to imagine and express an event that does not yet exist but arrives in advance. With the future, time gains meaning. Lastly, negation introduced the concept of truth and falsehood in logic. The proposition "p equals p" has no practical significance, but by introducing "not," we can distinguish the truth and falsehood of propositions, which also forces us to explain and assign values to things clearly.

Therefore, negation is not only a grammatical innovation but also a great explosion of thought, allowing humans to shift from merely describing the world to thinking more profoundly.

Moreover, from the perspectives of economics and phenomenology, there are reasons why nouns became the most commonly used word type in the early stages of language development. On the one hand, in primitive society, survival was the primary task. The effectiveness of information transmission was directly related to the survival and reproduction of the tribe. Nouns, with their highly summarizing classification attributes (a noun can represent a category of things), had the advantage in information economics and became the best carrier for information transmission, greatly improving the efficiency of information transmission. On the other hand, human cognitive abilities are limited, and thinking requires a clear focus. Therefore, we must simplify the complex real world into graspable objects. Static nouns can help humans clearly identify and focus on specific things, enabling humans to effectively process environmental information.

The Inherent Requirements of the Complex World: Transition from Static to Dynamic Cognition

The noun-centric language has provided us with a powerful ability to organize knowledge, but its most significant limitation is the inability to explain the dynamics, complexity, and emergence of existence. One reason why nominal logic is insufficient to understand dynamic things is that it fabricates a hierarchical order of existence based on the taxonomic idea order. Taxonomy, as the basic application of nominal thinking, provides us with a coordinate system for understanding the world. Humans quickly identify and accurately locate things by assigning specific value ranges to them.

The key question is: Are the classifications we make really based on the inherent attributes of things? Is there a purely objective classification method that is unrelated to human intentions? Once we review the classification systems in different cultures, we can find the relativity of nominal classification. Traditional Chinese classification methods focus on being people-oriented, that is, determining classifications based on the relationship between people and things, such as the division between beneficial birds and pests. This classification method may not be rigorous in biology but has guiding significance for human life practice. In addition, Chinese cultural taxonomy often uses the appearance of things as the basis for classification, and pictographic characters are an example. This "judging a book by its cover" tendency is more in line with human intuitive experience than the Western classification based on essential attributes. Therefore, whether taxonomy truly speaks of existence and whether things are allocated as they remain an unresolved issue.

Another major limitation of nominal thinking is that it attempts to form closed definitions of things. Based on taxonomy, nominal thinking further promotes the development of the conceptual system and formal logic. Concepts need to establish clear boundaries for each category of things to distinguish the inside from the outside. These closed conceptual boundaries provide a clear framework for cognition and also promote Western metaphysics centered around "to be."

"Is" (is) mainly has two meanings in philosophy: one is to indicate "classification," for example, "A belongs to B" or "A is greater than B," expressing the classification and hierarchical relationships between things; the other is to indicate the equivalence relationship between two things (equal). Analytical philosophy uses these two methods to logically reduce language, making it clearer and more understandable. This method is essentially analyzing language into a functional relationship, that is, understanding the relationships between things through "x=f(y)." However, such equivalence can only be achieved in a closed and static system. Strictly speaking, only mathematics can achieve true definition because mathematics creates concepts through definition and achieves a self-referential closed loop through a priori axiomatic constraints. However, the real world is dynamic, open, and even full of loopholes, and defining clear boundaries for concepts is just an idealized projection of nominal thinking.

Furthermore, if "is" is to express the relationship of "existence," it necessarily involves the proposition of "existence equals existence." This completely overlapping relationship requires the subject to contain everything and become a universal set that includes all sets, including itself. However, this will lead to the "universal set paradox" (that is, Russell's paradox - a self-referential universal set system will inevitably lead to contradictions). However, Western philosophy believes that under the premise of the existence of an omniscient and omnipotent God, this logical relationship can be established. God, as the universal set, is defined as existence itself, rather than an objectified existent. The saying "God is" avoids the self-referential paradox and maintains the foundation of ontology. This solution also reveals the underlying thinking of formal logic: it takes nouns as basic units and constructs a set-theoretic world. This is our most fundamental cognitive tool for understanding the world and has helped us achieve unparalleled knowledge achievements.

However, with the progress of science, especially the rise of emerging fields such as artificial intelligence and quantum mechanics, traditional nominal thinking has gradually become inadequate. Therefore, thought needs to add a new metaphysical dimension to reveal things hidden outside the traditional philosophical spectrum.

When we shift the focus of our thoughts from nouns to verbs, we will gain another description of the state of existence. The traditional nominal system has shown remarkable efficacy in the construction of static categories, accurately expressing meanings of certainty, stability, necessity, closure, and independence. However, it struggles to capture dynamic meanings such as causality, variability, uncertainty, possibility, contingency, openness, and continuity. The limitations of nominal thinking prompt us to seek an expression system that is more adaptable to dynamic interactions and complex systems, and the introduction of verb thinking may help to fill this gap.

Verbs as Metalanguage: A Collaboration Space for Mathematics, Logic, and Linguistics

Professor Zhao Tingyang believes that the relative weakness of human verb thinking can be traced back to the Old Stone Age, around 50,000 to 60,000 years ago. At that time, the most essential information needed for human's simple life was the identification and classification of objects, which led to the development of nouns as the core elements of language. In this process, verbs mainly served to provide hints and did not need to express complex dynamic relationships.

Despite the long-term dominance of nominal thinking in human cognitive development, by collaborating with mathematicians and logicians, we may be able to build a thinking system based on verbs, namely verb thinking. Mathematics, which expresses dynamic changes through functions, already has some elements of verb thinking. The verbs in it ("+" and "-") are defined very precisely, but they are only applicable to quantifiable parts and involve a much narrower semantic field than that of verbs. The dynamic relationships they can currently handle are very limited.

In logical calculus, nominal thinking and static reasoning still dominate, and "implication" is the only term that expresses dynamic relationships. It can effectively handle the transitivity of truth values ("A implies B"), but it cannot well express the causal relationships in the dynamic, empirical world. For example, "A implies B" is not equivalent to "A is the cause of B," because implication describes the reasoning from one proposition to another, while causal relationships involve more complex dynamic interactions, which are beyond the scope of the existing logical framework.

Leibniz once pioneeringly pointed out the limitations of formal logic and tried to make up for its shortcomings through the "principle of sufficient reason" (that is, any judgment must have sufficient reasons). However, the principle of sufficient reason relies too much on ontology and cannot be expressed within a strict logical framework. If we were to provide a completely sufficient causal explanation for a phenomenon, we could even argue that "the entire world" is the cause of this phenomenon, since no reason is sufficient to exclude the possibility of a factor as a variable. Therefore, this "sufficient reason" that cannot be fully expressed does not hold in the scientific system, although it does hold for God. Although this law is not very applicable to the empirical world, it inspires us to think about the shortcomings of the current nominal logic. The ontological ability contained in verbs may guide us towards a thinking structure that has not yet been fully developed.

Professor Zhao Tingyang suggests that we can reflect on language and knowledge systems themselves by drawing on Gödel-style self-reference. Gödel revealed that there are some propositions in the mathematical system that are "true" but cannot be proven within the system, thereby forcing the entire mathematical system to confront its own boundaries. This kind of structural reflection provides a paradigm that can be borrowed for the idea of verb logic. Given the open boundaries and loose structure of the humanities knowledge system, internal reflection needs to be achieved through building mutual reflection across knowledge systems, that is, using the external perspective of others to replace mirror-like self-reference. Specifically, this means using verbs as a metalanguage to reflect on nominal thinking. This approach does not require a consistent answer within a closed system but rather reveals the limitations of the original system by introducing the dimension of verbs.

The traditional knowledge system's metalanguage dilemma lies in the circularity of self-reference. All languages ultimately need to be explained through natural language, including mathematical language. When natural language assumes the function of a metalanguage, it is also an object to be explained. In this cycle, the core of the traditional language system is nouns, so the explanation also revolves around nouns. Therefore, when we try to use natural language to reflect on natural language, we are actually still explaining the nominal system with the nominal system. This practice plunges us into an infinite recursion of static definitions, lacking the power to step out of ourselves. Perhaps verb metalanguage (explaining nouns with verbs) can serve as a heterogeneous cognitive lever.

Professor Zhao Tingyang's idea is to construct a verb system that maps each noun to a set of related verb explanations, thereby giving the originally static, defined entities (what) a set of processual, dynamic interpretations (how) - we no longer focus on what things "are," but on how they "become what they are." Although this translation is not a strict Gödelian self-referential paradox, it has a similar reflective effect in function.

The Gödel paradox requires the system to face problems it cannot solve, while verb metalanguage reveals the content obscured by the current static dimension by introducing a dynamic dimension. This cross-dimensional mode of explanation is precisely the revelation and transcendence of system boundaries. In this sense, the nominal system is like a distribution map that marks the positions of things; the verb system is like a construction map that depicts how these things are formed, how they are related to each other, and how they continue to generate. Therefore, if traditional metaphysics attempts to "understand time in terms of space," then verb philosophy is trying to "understand space in terms of time."

This linguistic turn not only signifies a change in ways of thinking but also heralds a new cognitive paradigm revolution. During the Enlightenment, a knowledge system of "rational man" was constructed based on reason and nominal logic. Today, as the energy of this system is running out, we may be entering a new era of enlightenment.

In this new era, verb thinking may become the core tool for cognitive transformation, helping us better understand the increasingly complex world and providing a new thinking model and logical structure for cutting-edge fields such as artificial intelligence. At the end of the lecture, Professor Zhao Tingyang humorously pointed out that perhaps when we truly grasp the secrets of verb thinking and feed it back to artificial intelligence, we may be able to find a way to be "happily dominated" in future technological existence.

Written by He Qirui