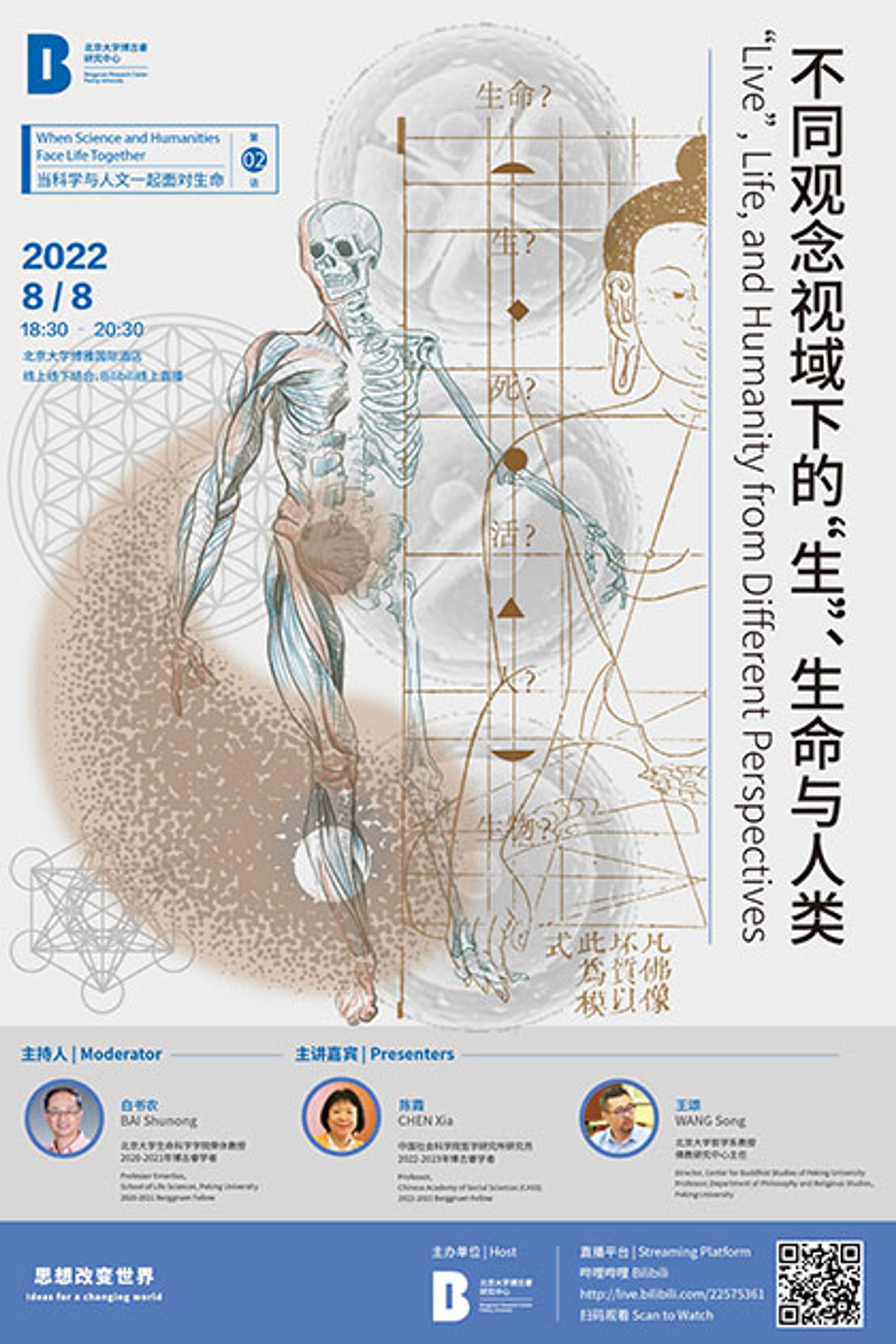

When Science and Humanities Face Life Together: Aliveness, Life, and Humanity from Different Perspectives

On August 8, the Berggruen Research Center at Peking University held the second workshop in its series “Living, Life, and Humanity from Different Perspectives.” This workshop was live-streamed on Bilibili to enable real-time audience interaction.

The workshop featured Chen Xia, a research fellow at the Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, and a 2022-2023 Berggruen Fellow; and Wang Song, director of the Center for Buddhist Studies and professor of philosophy at Peking University. These eminent scholars engaged in a philosophical dialogue, drawing from Taoist culture and Buddhist thought to address fundamental questions about the nature of life. This dialogue is moderated by Bai Shunong, professor at the School of Life Sciences, Peking University, and 2020-2021 Berggruen Fellow, moderated the discussion.

Before introducing the speakers, Bai Shunong reflected on the place of the Berggruen China Center in a turbulent world, calling it a “think reactor” with a strong commitment to the cross-cultural and interdisciplinary research between East and West that will be crucial for the future of human development.

The Taoist View of Life

Chen Xia delivered a keynote speech titled “My Perception of the Taoist View of Life,” sharing her understanding of the nature of life across five aspects. The first springs from a vision of the universe “like the mythical animal Kun-Peng spreading its wings” (鲲鹏展翅 宇宙视野). Referring both to the story of “a bow lost by a native of the Chu state is picked by another native of the Chu State” in Master Lv’s Spring and Autumn Annals; and the chapter “Free and Easy Wandering”(逍遥游) in Zhuangzi; Chen this described this highly particular Taoist view of the nature of life’s place in the universe.

The second concerns “the Tao produces everything, while the qi access the heaven” (道生万物 通天一气). According to Laozi, everything comes into being because of the Way. In other words, “the qi nourishes and creates,” continuously maintaining all that exists while accommodating all that is new. The story of “Chaos” told by Zhuangzi is an allegorical reflection on the evolution of the universe that has inspired some modern physicists. These ideas reveal that ancient philosophers seeking the unity among all things that physicists pursue, believing that they are either be unified by the Way or the qi. By contrast, noted Chen, the Tao is a more fundamental source than the qi when it comes to creation.

In addition to exploring the origin and nature of life, humanistic scholars reveal more featured thinking on how life should be. Chen focused on answering how we should spend life after it comes into existence. Her third aspect of the nature of life elaborates on the philosophical question of which is more important? One’s two arms or the power to rule the state (两臂天下 孰重孰轻). Taoists attach great importance to life, holding that it is invaluable in the universe. Chapter 13 of the book Laozi says,

“Thus those who value the care of their own persons more than running the world can be entrusted with the world. And those who begrudge their persons as though they were the world can be put in charge of the world.” (trans. Roger Ames)

This indicates that power comes from people’s trust; the people entrust the state to rulers who cherish life. Attaching importance to life, Laozi firmly opposed warfare:

“Military weapons are inauspicious instruments. And so when you have no choice but to use them, it is best to do so colly and without enthusiasm…When the casualties are high Inspect the battleground with grief and remorse; When the war is won,Treat it as you would a funeral.” (trans. Roger Ames)

Taoism proposes that life should be “self-adapted and tolerant of things” (“自适其适 宽容于物”) and that each individual is unique and irreplaceable. By “self-adaptation,” Zhuangzi meant to adapt to oneself, to be consistent with oneself, and comply with the nature of the subject. It is as Johann Gottlieb Fichte mentioned in the book The Vocation of Man (German: Die Bestimmung des Menschen): “the ultimate and highest goal of man is the complete self-adaptation of man.” The Taoists have compassion for everything in the world.

As another saying goes:

“(the sage) is always skillful in elevating people. Therefore she does not discard anybody. She is always skillful in helping things. Therefore she does not discard anything.” (trans. Charles Muller)

The Taoists will not refrain from saving any human being or any other thing. Genuine altruism demands treating others as a purpose instead of a means or a tool.

Thirdly, to adapt life to the self requires the conditions for inaction; in other words, the ideas, honored by the Taoists, to follow the natural flow of Tao, and to govern by doing nothing that goes against nature. In saying that that “great perfection seems flawed”(大成若缺), Laozi reflected a deep sympathy for and understanding of humanity’s imperfections and weaknesses. Humanity’s flaws are natural. A human being, a life, and a livelihood are essentially imperfect. The Taoists pursue a simplistic life of returning to the unpolished and the genuine. A distinctive feature of the Taoist view of life is to be “easygoing and carefree” (you游). An easygoing and carefree attitude towards life reflects the use of the useless. This is not the same thing as “lying flat,” or refusing to serve society. It is about utilizing an aesthetic attitude in behavior self, others, and things. Zhuangzi himself was a role model of living an easygoing and carefree life. The notion that “within our realm there are four greatnesses, how small it [humanity] is!” reflects the Taoists’ highly intentional attitude towards “humanity.” Chapter 25 of the book Laozi reads,

“Way-making is grand,

The heavens (tian) are grand,

The earth is grand,

And the king is also grand.

Within our territories

There are four “grandees”

And the king occupies one of them.

Human beings emulate the earth,

The earth emulates the heavens,

The heavens emulate way-making

And way-making emulates what is spontaneously so (ziran). ” (trans. Roger Ames)

Among the four grandees together with the Heaven and the Earth, humanity is highly subjective, but such subjectivity does not make humanity arrogant. The book Zhuangzi stresses that “How insignificant and small is (the body) by which he belongs to humanity!” (trans. James Legge) As a highly limited existence, humanity should treat others and things with humility and conduct themselves in gentle ways that may triumph over rigid and strong obstacles or ways of being.

Fourth, “as life and death are in unity, one should satisfy and comply with nature.” Death is unavoidable for any life. The Taoists regard that life and death are in unity, and one should treat life and death as a natural process throughout the journey of life.

Finally, “one should walk out of the center, as all things are equally regarded.” The Taoists, while pondering over life, also take into account all things. The book Zhuangzi abounds in stories about dialogues with animals and plants, the most representative ones including “Zhuangzi Dreams of a Butterfly” and “The Debate Between Zhuangzi and Huizi on the Fish’s Joy.” Such relationships go beyond the protection of animals and reflect humans living in harmony with all other living beings.

“Aliveness” (Sheng 生) in the Buddhist Perspective

Wang Song then delivered a keynote speech entitled “‘Alive’ in the Buddhist Perspective: Life and Humanity.” This ideas consists of six aspects. The first is about life and living things: How should one examine the question of whether life and living things are the same from the Buddhist perspective? The second is about the relationship between non-self and self. The third is about Buddhism’s basic attitude towards living creatures: What are the historical foundations for occurrences such as abstaining from taking life, protecting life, and freeing captive animals? The fourth is about the Buddhist altitude towards human life: What is the relationship between the seemingly contradictory ideas of sacrificing the body, and cultivating the body? The fifth and sixth are about two related dimensions: what drives the continuity of life, and what is the meaning of the continuity of life?

First, the speaker noted that “life” (shengming 生命) is different from living things. A living thing is what we generally call a phase of life, that is, a being combining body and spirit, which complies to the law of origination of birth, dwelling, deterioration, and destruction. Life itself continues by means of reincarnation. This present life is only one phase of life, and it will continue to exist through reincarnation. When Buddhism talks about “once in a lifetime,” it refers to one phase of life. Such a concept of reincarnation is not peculiar to Buddhism; the idea of reincarnation existed early in Aryan civilization. Buddhism has further added the concept of “perception” to reincarnation, that is, a subject of life that repeats without end has enriched the concept of reincarnation.

The second is about non-self and the cycle of life. In Buddhism, the concept of “self” is not real; instead, it is made up of a series of factors, each of which is a “cause” but not the complete form of “self.” The “self” can be divided into the Five Aggregates and the Four Great Elements; in this sense, the “self” is the subject presented in one phase of life. The subject of reincarnation of life, or perception, is driven by ignorance, power of karma, and law of causation, as it repeats the phenomenon of reincarnation of life. Among them, causation is a highly simplistic law. It is utterly simplistic and profound: “It is here and therefore it is there; it arises here and therefore it arises there.” Under the effect of the relationship of mutual generation and treatment, life reincarnates from one phase to another.

The third is about revering life, abstaining from taking life, and protecting life. We want to emphasize that Buddhism, which originated in India, has been influenced by Indian culture. Abstaining from taking life is a common doctrine of Indian culture. To this day, Jainism holds abstaining from taking life (ahiṃsā) as one of its most significant doctrines. Another reason for “abstaining from taking life” is the six paths of reincarnation. The precepts in the Sutra of Indra’s Net are the basis for vegetarianism in Chinese Buddhism. Wang Song concluded that there is an evolution of the idea of protecting life in Buddhist classics. From the simple karma with one consequential result for one’s acts to the concept of compassion, from the simple self-consciousness to the consciousness of the relationship between the self and the others, such a feature is highlighted in the development of Mahayana.

The fourth is about the relationship between sacrificing the body and cultivating the body. Buddhism starts by shattering the attachment to the present world. According to Buddhist theories, one should neither cling to life nor crave for the body, but should sacrifice the body for a higher goal, just like the story of the Buddha sacrificing his body to feed a tiger. Meanwhile, Buddhism has also absorbed the traditions of Indian yoga and tantra. In China, it absorbs the traditions of Taoism, with a strong emphasis on cultivating the body. A significant manifestation of an eminent monk in the secular world is a long lifespan. The Buddhist dialectical approach to sacrificing the body and cultivating the body is, in layman’s terms, neither to cling to nor to squander the body. Although it is the “vile skin-bag” (a Buddhist term for the human body), it is also the pillar of our spiritual strength.

The fifth is about continuing and powering life. Buddhism believes that the external driving force of life (the superior cause) is sex in the biological sense. In Hinayana, the first stage of Buddhism, Buddhists believe that life is the root cause of suffering. Life appears because of the action of sex, and the abstention from sex in the precepts is to sever the external impetus of reincarnation. Mahayana goes beyond Hinayana’s insistence on renunciation and considers too much emphasis on this aspect a form of obsession. Therefore, Mahayana teaches that there are no differences between getting involved in society and standing aloof from worldly affairs. Birth and death are the same as nirvana, while sufferings are essentially Bodhi. In a strict sense, Mahayana does not oppose sex itself, but rather evil lust, and advocates controlling desire with abstinence; it is taken as a process of cultivation.

The sixth is about the meaning of continuing life. Philosophy and religion have ceded to science the right to speak on the question of what the world is like, but it is the value of philosophy and religion to question and reveal the meaning of the world. A phase of life follows the basic law of karma, which is featured by impermanence in phenomena, i.e., birth, dwelling, destruction, and dissipation; all living beings are no exception. In that case, does life have any meaning or not? Simply speaking, each phase of our life appears to greet its birth, dwelling, destruction, and dissipation. It is seemingly meaningless, but the overall process of reincarnation of life as a whole is absolutely meaningful. To summarize, the basic Buddhist view of life can be divided into two dimensions: body and mind. At the level of the body, the Four Great Elements of earth, water, fire, and wind are the biological elements that constitute the first phase of life, which complies with natural properties and features impermanence. Its specific process of change, also known as transformation, has no special meaning. It is characterized as “obvious and coarse” and easily perceptible. At the level of the mind, our consciousness is more “hidden and subtle,” which needs to be grasped, understood, and recognized through meditation. It flows back and forth, with social properties and meaning. Birth and death are the processes of gathering and dispersion of the Five Aggregates. From Hinayana to Mahayana, we can see the improvement and leap from existence to co-existence, from self-interest to altruism.

How Science and Humanities Observe the World

In the dialogue session, Bai Shunong began by sharing some of his insights about what the keynote speeches. Taoism manifests a questioning spirit. During the Spring and Autumn and Warring States Period (770-221 BC), when all parties were vying to grab land and power, the Taoists stood up and asked: Is this necessary? There is also a transpersonal view of the universe. We now have different perspectives on the world. How can we genuinely understand what the world itself is from different perspectives? If Zhuangzi had been a prime minister, there would have been less “free and easy”(xiaoyao 逍遥) matters in the treasure stove of human thought. Such “free and easy” matters are a significant force for the balance of mind and of society.

Next, Bai Shunong asked Chen Xia the question: Is there a bottom line to the frugality advocated by Taoism? Chen Xia replied that both Laozi and Zhuangzi criticized excessive desire. Laozi advocated “lessening selfishness and decreasing desire,” while Zhuangzi said, “When the tailorbird makes its nest in the deep forest, it doesn’t use more than a single branch. When the mole drinks from the river, it fills its belly, and nothing more.” (trans. Charles Muller) Chen Xia believes that it is necessary to promote a simplistic life, and maintain an unpolished and genuine way of being in modern society. Zhuangzi’s idea of “losing oneself in things” is about people who are obsessed with the things they own so much that they lose themselves instead. If one pays excessive attention to possessing external things, to some extent, how could he or she be not possessed by these external things? Have we not been possessed by cars, houses, and luxury goods? Excessive consumption comes at the cost of damaging the environment. Human desires are endless, but natural resources are limited. We are facing many serious environmental and ecological problems, especially global climate change, so human beings need to take responsibility for life, exercise self-restraint, and reduce consumption and waste. After our basic living needs are fulfilled, we can use the remaining resources to enrich our spirit. Spiritual products do not decrease by sharing, but rather increase.

Finally, Bai Shunong posed a question to Wang Song: “What is the meaning of life in Buddhism?” Wang Song noted that modern society emphasizes the rights of the individual and that modern civilization is based on the recognition of individual values, whereas previous values were often based on external transcending acts or groups. The Chinese often say that we should bring glory to our ancestors. An important embodiment of civilization is the consciousness of individual sacrifice. Only a behavior that pays a price is moral. Now there is the problem: Why should we sacrifice ourselves for the sake of others? Buddhism, like other values, emphasizes the perception of the small self and the big self and believes that the value of life is in the cycle of reincarnation. The basic value is self-liberation, while the advanced one is Bodhi. In other words, the two kinds of value represent self-interest and altruism, respectively. Self-interest is to free oneself from the suffering of reincarnation, while altruism is to bring liberation to others and make them attain enlightenment. This is the basic value.

The dialogue lasted for nearly three hours, in which the guests had a fascinating conversation about many issues. It aroused active responses from the audience, both on-site and online.

Recorded by: Yu Han, Schwarzman Scholar, Tsinghua University.

Interviewed and written by: Cao Yueyang, doctoral candidate, School of Social Sciences, Tsinghua University