Weekend Roundup: How Nations Surmount Upheaval — or Don’t

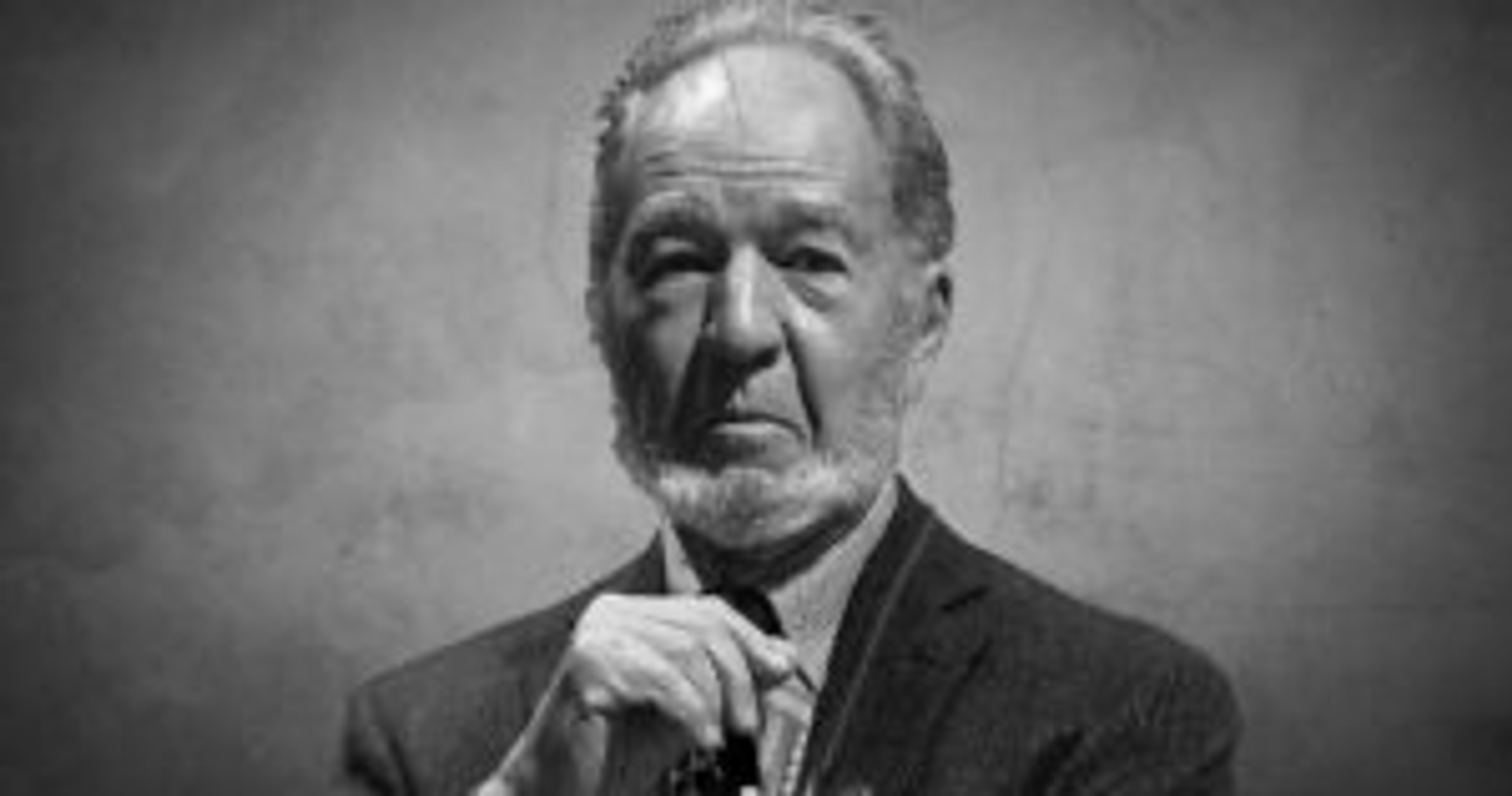

Jared Diamond, author of “Upheaval: Turning Points for Nations in Crisis.” (CC/WorldPost Illustration)

From refugees on the move en masse to populist revolts, trade wars and digital disruption, turmoil is roiling all nations. At the planetary level, the cascading consequences of a warming climate are melting the ice caps and fomenting extreme weather. It is sometimes difficult to imagine how we can ever overcome this perplexing welter of crosscurrents and daunting challenges.

In an interview with The WorldPost this week about his new book, “Upheaval: Turning Points for Nations in Crisis,” Jared Diamond offers some historical lessons on how such challenges were successfully met — or not — in the past.

In assessing how nations manage crisis and negotiate turning points, he passes their experience through several filters: realistic self-appraisal, selective adoption of best practices from elsewhere while still preserving core values and flexibility that allows for social and political compromise. Diamond also emphasizes how a common sense of belonging is a key factor that enables nations to successfully adapt to new realities and surmount obstacles, but at the same time frustrates the ability to address global issues.

Nations exhibit different qualities at different times, or fail to do so, to their benefit or detriment.

For example, Japan successfully modernized by adopting Western industry and legal codes during the Meiji reforms of the late 19th century — while at the same time maintaining its civilizational identity. But then, after it was the first Asian nation to defeat a Western power in the Russo-Japanese war, military leaders who “learned the wrong lesson” gained influence, leading decades later to disastrous defeat resulting from its ill-fated attack on America.

“Realistic self-appraisal was lacking for a particular reason,” says Diamond. “In the Meiji Era, the reformist leaders had all been to the West after the opening of 1853. One of the first things that Meiji Japan did was to send out an observer team that spent a year and a half going around the West and studying best practices. They made a conscious effort to learn from the West. In the 1930s, many of those in the Japanese military who took control had not spent much time in the West. Yamamoto, who had been the naval attache to Washington and knew better than to risk challenging America’s industrial capacity that dwarfed Japan’s, warned, to no avail, against the consequences of the Pearl Harbor attack.”

A lack of realistic self-appraisal, I suggested in our conversation, might describe how the U.S. and China have come to blows in the trade war. While Deng Xiaoping followed the notion of “bide your time and hide your strength” as China developed, Xi Jinping has discarded any such restraint and boasted that the Middle Kingdom had returned to the center of the world stage and would even overtake the U.S. in technological supremacy. This proved too much for the Washington foreign policy establishment, no less Trump and his team, who are fighting back with a trade war.

Xi’s mistake, from the standpoint of China’s interests, is that he seems to have moved too soon and exposed his nation’s key vulnerability — its high-tech advances still depend heavily on the West for semiconductor chips and other technological inputs.

Diamond’s reply: “What was true of the Japanese militarists and may be true of Xi as you suggest, also applies to the U.S. today — people’s mindset, the narrative they choose to believe, often overrides their perception of reality and the facts in front of their faces. This is likely true of the virtual paranoia many Americans feel today about China and the prospect of an Asian Century in which it dominates. … What matters is whether those in charge in the governing class share a worldview based on knowing the world, not just part of it that fits with their inclination.”

Another parallel discussed in his book is how Chile, once the most stable democracy in Latin America, descended in the 1970s into the kind of intense polarization and incapacity for compromise we see in the U.S. today. In Chile’s case, that led to a brutal military coup and 17 years of dictatorship.

What we see in both cases, says Diamond, “is a process of erosion that at some moment reaches a point of no return.” But there are obvious differences. “If democracy ends in the U.S., it’s not going to be the way it ended in Chile with a military coup. It will end through a slow erosion, a continuation of trends we see now of restrictions on the ability of people to register to vote, on low voter turnout, on the executive interference with the judiciary and struggles between the executive and the Congress. I don’t take it for granted that democracy in the United States is going to overcome all obstacles. I see a serious risk.”

Are there cases in which nations have anticipated crisis and avoided it? Yes, argues Diamond. A case in point is the European Union, which has sought to integrate sovereignties as a way to defang the aggressive nationalism that decimated the continent in two world wars during the 20th century. Many today, lamentably, are poised to unlearn that lesson.

On the other hand, he notes, paradoxically, strong national cohesion is “what has enabled nations to face and surmount crisis through a sense of common identity that can mobilize allegiance to a course of action. Today, especially given the revival of nationalism, there is no such solid global identity. That is the chief challenge in battling climate change.”

Yet, even despite that absence of a planetary identity, overcoming some key global challenges has proven possible. “In fact,” Diamond observes, “the world has a track record over the last 40 years of having solved really difficult problems in diffuse and unflashy ways — for example, eradicating small pox. To eradicate the threat of small pox contagion, you had to eradicate it in every country in the far reaches of the world, including Somalia, where the last cases appeared.”

This last point suggests that we may have entered a new era in which common challenges can be addressed through networks that cross boundaries and are neither national nor global.

“For massive change to take place,” the polymath designer Bruce Mau has observed, “it doesn’t have to cross the classical, formal political threshold. The single biggest difference between the past and the future is that the capacity to affect change is ‘distributed.’ A new social and political ecology is evolving where individuals or groups don’t have to go up the tree of political authority only to come back down again and make something happen. That is inefficient. They can do it on their own, through interconnectedness with others.”