Imaginaries of Immortality in the Age of AI: China

- Date: April 21, 2025

- Location: Berggruen Institute China at Peking University

From April 21—25, 2025, the Berggruen Institute China hosted the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence at Cambridge University, and conducted a cross-cultural research project on “Digital Immortality.” Based on China’s cultural background, the project explored various social and cultural imaginaries related to AI-driven concepts of immortality, examining how Chinese philosophy, folk customs, and practices guide and shape the development of digital immortality technologies and industries in the digital age, as well as the ethical considerations this raises.

“Digital Immortality” is a series of research projects aimed at exploring how this concept manifests across different cultural contexts. Previously, the Cambridge team—Dr. Katarzyna Nowaczyk-Basińska, Dr. Stephen Cave, and Dr. Tomasz Hollanek—had already completed related research in Poland and India.

This project in China included one expert workshop and three focused groups.

Expert Workshop: Existence, Reality, and Belief in the Digital Age

On April 22, the expert workshop was held at the Berggruen Institute China’s office at Peking University, bringing together an interdisciplinary group of experts whose work spans journalism, philosophy, law, art, technology, and end-of-life care in China.

Participants included Dr. CHEN Xia, a Daoist philosopher from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Professor SUN Xiangchen from the School of Philosophy at Fudan University, Professor DAI Xin from Peking University Law School, Mr. LIU Yan, founder of Beijing 6Rooms Technology Limited Company and one of the earliest practitioners of “digital immortality” products, Director QIN Yuan from the Palliative Care Department of Beijing Haidian Hospital, Dr. CHEN Meixia, Leader of an elderly care focused NGO, researcher YANG Liang from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, artist CAO Shu, and independent journalist ZHOU Boya (read Zhou’s article about her personal experience of the project).

The first session was moderated by Dr. Stephen Cave from the Cambridge team and SONG Bing, Senior Vice President of the Berggruen Institute and Director of the Berggruen Institute China. This session focused on exploring China‘s unique cultural background, particularly concentrating on China’s philosophical traditions—Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism. Although these traditions often interweave in complex ways, collectively forming the underlying concepts of Chinese culture, each tradition provides a unique perspective through which the experts examined the concept of “digital immortality.”

Dr. CHEN Xia pointed out, from a Daoist perspective, life is an unrelenting pursuit of various forms of “longevity and immortality.” From this standpoint, “digital immortality” can be viewed as one of many manifestations of this pursuit—a broad path on the journey toward transformation and transcendence. Buddhism, on the other hand, emphasizes the importance of letting go of worldly desires and attachments—based on this principle, digital life technologies that promise an afterlife might be seen as distractions on the path to enlightenment. Confucian thought places great importance on ancestral lineage, social relationships, memory, and filial piety. Within this framework, digital immortality can be viewed as fulfilling traditional obligations to the deceased through emerging technological tools—preserving memories and maintaining intergenerational connections.

In attempting to define the concept of “digital immortality,” experts drew attention to its dynamic, computational, and non-biological characteristics, identifying data and memory as its key elements. “Digital immortality is not authentic—it’s a metaphor,” argued law professor Dr. DAI Xin. Building on this, tech researcher YANG Liang added, “It’s not so much about what we perceive, but what we believe”. Dai further clarified, “Digital immortality is a form of immortality through other people. It’s all about interaction.” LIU Yan, one of the earliest practitioners of “digital immortality” products, agreed with this viewpoint, noting that this form of immortality exists only from the user’s perspective—what remains is not the person themselves, but a simulation; the subject has already disappeared. These reflections collectively point to key questions about existence, reality, and belief in the digital age.

Dai also warned that a major risk in the development of the “digital immortality” industry is that it could lead to a loss of control over personal narratives, thereby raising ethical concerns about people being digitally “resurrected” without consent. Other experts held similar views. Yang pointed out that “adopting these technologies on an individual level may be much easier than achieving broader societal acceptance,” highlighting the cultural and ethical complexities of the latter. QIN Yuan, Director of the Palliative Care Department of Beijing Haidian Hospital, emphasized that any meaningful continuation of the self must include both physiological and psychological dimensions, with the latter involving both consciousness and the unconscious. Without these fundamental connections, digital personalities would be mere projections of the deceased. Additionally, some experts expressed cautious concerns about the commercialization of digital immortality—especially considering that China’s funeral industry remains relatively less privatized compared to many Western models.

A Speculative Exercise

These reflections laid the foundation for the next segment: a speculative exercise moderated by Dr. Tomasz Hollanek from the Cambridge team. Designed to be both engaging and thought-provoking, the exercise invited participants to step into the role of consultants for a fictional U.S.-based tech company planning to launch a digital immortality product in China. Hollanek acted as the company’s representative, prompting experts to evaluate the product’s features and critically examine the cultural values and assumptions embedded within its design.

This segment used realistic participation and hands-on experience to stimulate experts to reconsider the problems digital immortality technology would face once it enters reality. They emphasized the importance of rigorously assessing user dependency and expressed concerns about the psychological impact of such technologies—especially on users in grief. Additionally, the reliability of private companies was questioned. Many experts suggested that digital immortality technology should be grounded in religious or philosophical traditions rather than being viewed as a profit-oriented business model. The experts believed that rather than exploiting human vulnerability in the face of life and death, the profits generated from this process should be invested in public welfare—the righteous path aligned with public sentiment and morality would be to position this technology as non-profit, rooting it in collective care, cultural sensitivity, and social responsibility rather than commercial interests.

In the subsequent segment, Dr. Nowaczyk-Basińska invited attending experts to envision ideal end-of-life scenarios with future AI. The experts were divided into two groups for brainstorming sessions. Their thinking extended far beyond “recreating the deceased” (making the deceased “digitally alive” by reproducing their voice and image)—a finding that coincided with the results of previous Cambridge team workshops in Poland and India.

One group believed that AI is not meant to replace grief but serves as a new channel of wisdom—capable of transmitting spiritual and ethical teachings,drawing inspiration from historical figures like Jesus and Buddha.The second group proposed a vision of AI as a tool for cultivating a deeper and more conscious engagement with death and dying—encouraging introspective reflection rather than escapism. According to this vision, AI should become a non-profit, abstract spiritual resource dedicated to serving the living, helping them face death with greater awareness. As SONG Bing summarized, “It could support a new form of education aimed at helping people cultivate a habit of thinking about death.”

In the workshop’s final segment, Nowaczyk-Basińska introduced an original concept for raising industry standards in the digital afterlife sector. She proposed establishing a team of academically knowledgeable experts who would receive specialized training to navigate the ethical and practical complexities of afterlife technologies. The need for this industry primarily addresses two urgent issues: first, creators of digital immortality technology often lack professional knowledge related to death; second, the reliance on “trial and error” approaches in developing such products and services is often disconnected from concrete life experiences. The presentation highlighted key arguments from her article “Digital Afterlife Leaders: Professionalisation as a Social Innovation in the Digital Afterlife Industry,” published in the special issue “Innovation at the End of Life” of the journal Mortality.

The workshop’s findings showed that experts unanimously agreed: managing posthumous data requires a new emerging profession with specialized training. Combined with findings from previous workshops in Poland and India, we can preliminarily conclude that the call for professionalization is gaining increasingly cross-cultural support. While survey data is still being further analyzed, there are already indications that people are both enthusiastic about this prospect while also aware of the structural challenges this technology’s development may face.

Art Works on Death

Artist Cao Shu introduced his work “Contains It Like Lines of A Hand,” a computer game–based project inspired by his mother’s recollections of his grandmother. In this piece, Cao reimagines his grandmother’s scent-based memories through a digital avatar that journeys through her digestive system. By doing so, he challenges conventional practices in memorial representation—typically reliant on voice or image—by highlighting the evocative potential of other senses, such as touch and smell.

He also showcased his project “Diffusion,” which was influenced by archival materials on the nuclear bombing of Nagasaki. This work prompted him to reflect on the intersection of photography, image-generation technologies, and memory of the deceased. In “Diffusion,” Cao explores the dual role of light—as both a creative and destructive force—questioning the technological mechanisms that shape remembrance and erasure.

(Im)mortality Over Dinner: Predicting the Side Effects of AI Mourning Technologies

The hosts held three distinctly different focused groups over dinner at carefully chosen venues, each yielding different insights. Participants for the focus groups were recruited through an open call posted on the Berggruen Institute’s WeChat platform.

Group 1

The first dinner was held at Yuhuazhai Zhongguancun Restaurant. Yuhuazhai is a non-profit charitable organization influenced by Buddhist principles that provides free lunch to community elderly, and offers hospice care services to critically ill seniors. Dr. CHEN Meiqin, who heads the Restaurant, and her team also conduct the “Voices That Cannot Wait” initiative, recording oral histories of community elderly to share and preserve their spiritual legacies.

During the dinner, participants discussed about the stories about their deceased relatives and friends. Interestingly, this marked the first time in our series where participants spoke about the dead not only with reverence but also as a source of pain and negative impact. Some participants shared experiences of intergenerational violence, and maintaining contact with the deceased would mean actively breaking cycles that had been harmful to them. Other participants discussed topics such as unconditional love, the eternal presence of deceased loved ones, and how “life and death form a continuous whole rather than an absolute division.”

A recurring idea throughout the meal was that “digital immortality” products would disturb the peace of the deceased. One participant explained: “In China, even during the Qingming Festival, the dead and the living do not coexist. The door must remain closed.”

One of the eldest participants at the table cautioned that this technology might erode traditions that have existed for thousands of years. She emphasized that “every family has its own unique ecology, and without these contexts, it’s impossible to construct a person’s complete digital personality. Moreover, such attempts might lead to chaos within families, which could trigger social-level turmoil.” Another risk is that these products might make grieving relatives unable to break free from their attachment to the deceased. This concern echoes a conclusion the Cambridge team reached during their activities in Poland: if such technologies were to be applied clinically (such as in grief therapy), they would need professional supervision and regulation to mitigate potential negative psychological consequences.

Participants generally agreed on the necessity of establishing regulatory frameworks. One attendee suggested that the government should play a central role. Another participant advocated that such technologies should be strictly excluded from commercialization, militarization, and politics.

Groups 2 & 3

The other two dinners were held at the Berggruen Institute China’s office at Peking University and Yiyuan Chinese Restaurant in the Global Village of Peking University respectively. Both dinners were filled with emotional intensity and intellectual exchange. For several guests, the dinners provided rare opportunities to mourn deceased loved ones. At the Berggruen dinner, some participants held strong skepticism toward the idea of using AI technology to “communicate” with the deceased. One attendee said: “I don’t want to use AI-generated digital avatars to commemorate the deceased. Actually, I don’t want to rely on any concrete objects to express mourning—I want to avoid attachment.” Another participant added: “This would destroy our memories of the deceased. We should let them rest in peace. According to our traditions, we also shouldn’t cry too sorrowfully for the deceased.”

Regarding whether it’s necessary to introduce AI mourning technologies as auxiliary tools in clinical treatment, Chinese culture provides a unique insight: any medicine that can cure and save lives also carries certain toxicity. This leads us to consider the side effects of AI mourning technologies. One participant suggested using such products on specific days, such as the anniversary of the deceased’s death, or during the Tomb Sweeping and Zhongyuan Festivals, as a form of remembrance; another participant suggested using them as archives for family stories, though he ultimately stated: “Perhaps being able to forget is also a blessing.”

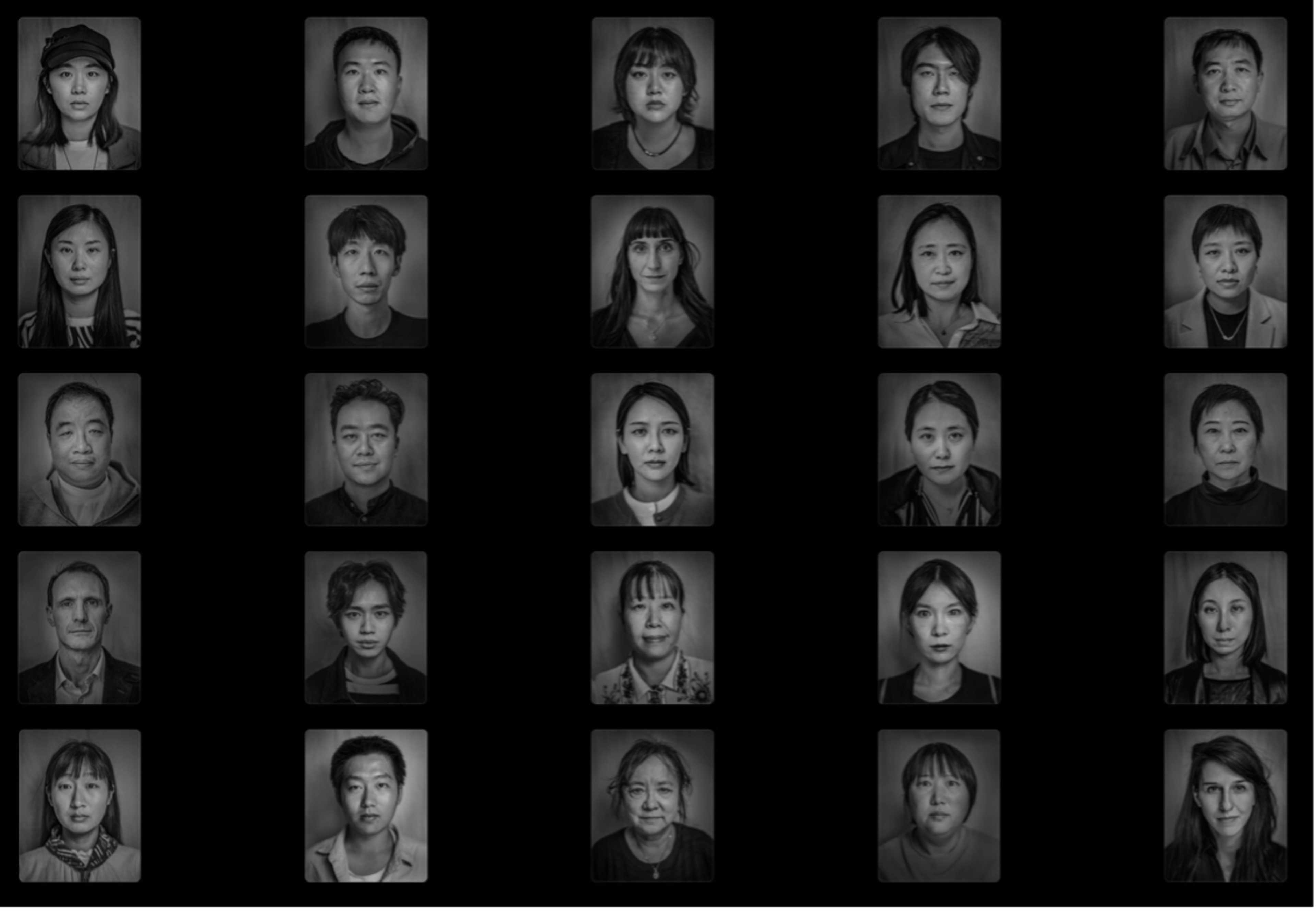

Personalized photography services provided for participants at this event.

Thanks to Anja Franczak from the Institute of the Good Death, photographer Tomasz Siuda, project research assistant Dr. Saide Mobayed Vega, and professional translator JIANG Lu for their strong support of this project.

Written by: Katarzyna Nowaczyk-Basińska, Saide Mobayed Vega

Photography: Tomasz Siuda

Edited by: Nick Corvino, MA Jian, ZHANG Chang, LI Xiaojiao

Read the original: https://katarzynanowaczykbasinska.pl/report-event-china/