Civil Unrest: Lessons From the Past

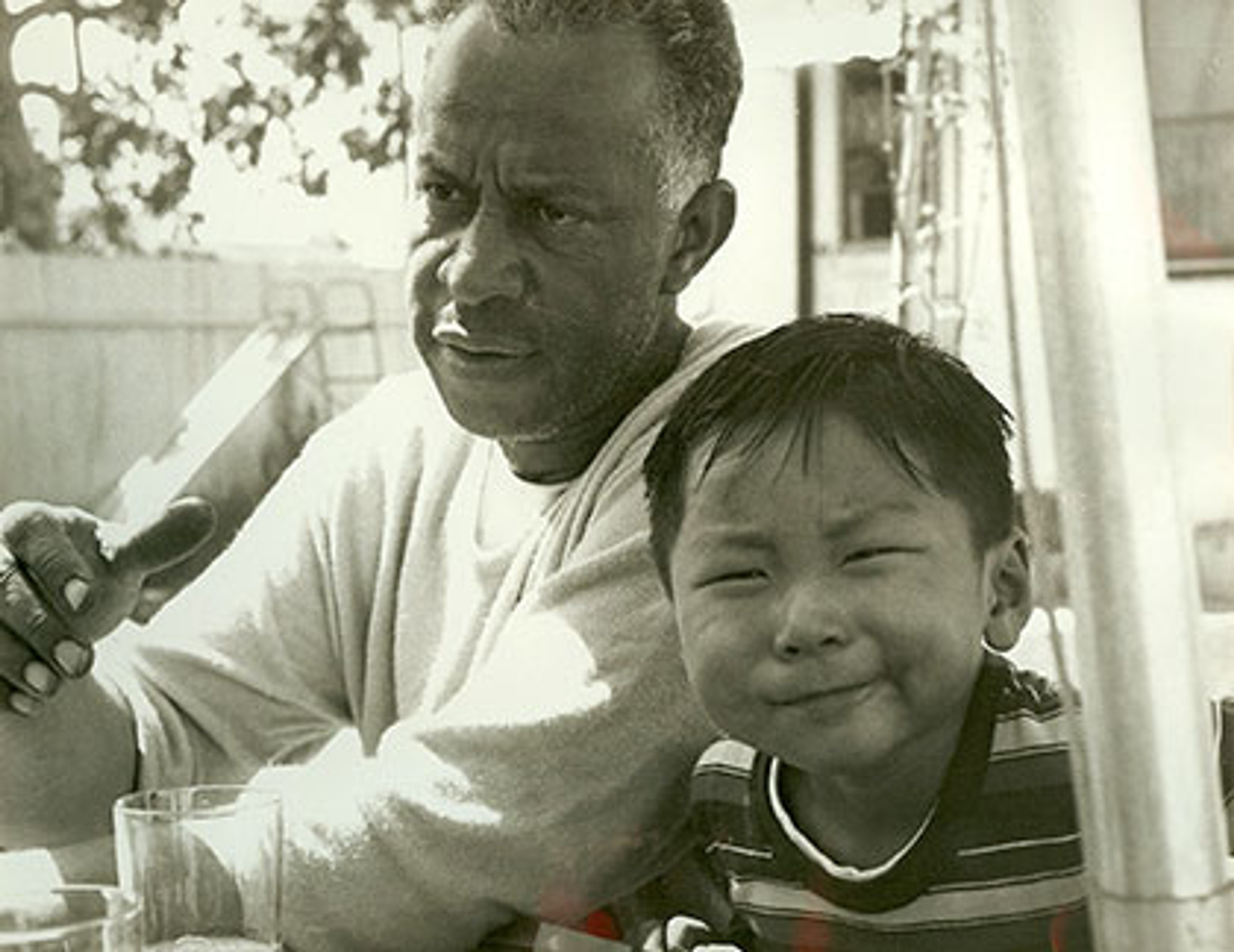

Emile Mack was a post-Korean War orphan, adopted by a South-Central Los Angeles African American family.

In trying to understand the African American experience and the current unrest, I have begun to look at the history going back to 1865. While the end of the Civil War led to the abolition of slavery, giving African-Americans freedom, it didn’t produce equality. In fact, it was not until a hundred years later, after much protest and civil action, that the Civil Rights Act of 1965 gave African-Americans, other people of color, and women equal status under the law.

But even that law did not produce what I describe as “equality of lives” for African Americans. With freedom from slavery, then equal rights laws, African Americans today still see their lives are not equal in comparison to Caucasians and others.

The country’s repeated episodes of civil unrest occur at the intersection of incidents of egregious visuals of police use of deadly force and the African American community’s commonly held underlying feelings of inequality, injustice, racism, and discrimination. The unresolved feelings creates an ever-present tension, that simply awaits a spark from anyone of a number of police use of deadly force incidents that ignite these tensions.

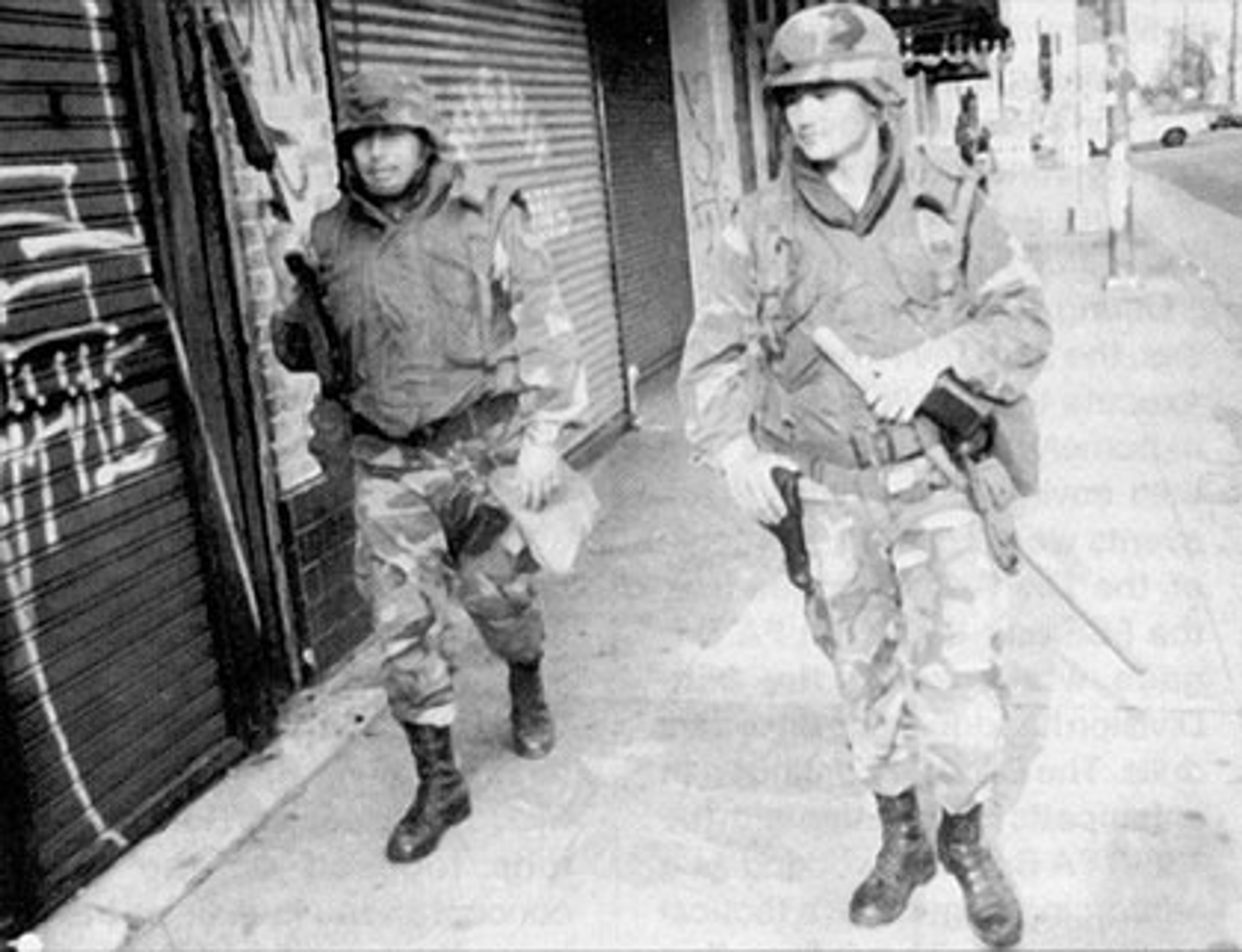

I was adopted from Korea and raised by an African-American family. We lived at Jefferson and 8th Avenue in Central Los Angeles. One of my early childhood memories is from the Watts Rebellion of 1965, seeing military tanks going down our street. Obviously at the time I didn’t quite fathom truly the significance of the event, but it made a lasting impression.

Police violence and African American racial inequality, intersected in 1965 and again in 1992. What sparked the events again in 1992 wasn’t just the injustice of the acquittal of the officers who had beaten Rodney King, but it again touched the African-Americans underlying feeling of inequality, discrimination, and racism. And again, in 2020, the feeling is the same as we hear African-Americans expressing the same underlying frustration.

Last week, amid the unrest, I was invited by Pastor Boyd of the First AME Church in South Los Angeles to a meeting of African American leadership. Mayor Eric Garcetti was there, along with Police Chief Michael Moore and Chief Alex Villanueva from the Los Angeles Sheriffs Department, and representatives speaking on behalf of the Nation of Islam and Black Lives Matter. Besides the obvious point of the police, the common thread, repeated over and over, was: inequality, discrimination, and institutional racism. I was there representing the Korean American Federation. I expressed that the African American and Korean American communities realized after 1992, we must build a strong relationship as we both understood that the long existing inequality for the African-American community has not changed and there is the real potential for another unrest.

Ricky Bonilla / CC BY-SA

Still, the 2020 unrest is very different this time than it was in 1965 or in 1992. During the 1992 riots, I was working for the Los Angeles City Fire Department (LAFD). In responding to the fires that burned across the city, I personally witnessed a great deal of violence, including a shootout between rioters and Korean-American shop owners. The intensity of the 1992 unrest was far different than 2020. In 1992, there was intense anger. It was a spontaneous eruption of violence and destruction that I saw envelope South Central and spread to Downtown, and on to Koreatown.

Today, in 2020, we have a more cause-driven response. People across the country are seeing the injustice in the video of the police caused death of George Floyd, and everyone agrees it needs to be rectified. So now there are people across the country, not just African Americans, marching and protesting.

Here in Los Angeles, it’s been much less violent than in 1992. We don’t know all the reasons for this, but hope our efforts we have taken from what we learnt from the past have contributed. First, our communities have reached out to each other much more. After 1992, we wanted to ensure that when unrest occurred again, the communities would be in direct contact, so that we could help resolve issues quickly, and avoid the conflict between the different ethnicities that occurred in 1992.

As the events related to the death of George Floyd unfolded, I called Pastor Boyd, First AME Church. I was calling the Filipino SIPA organization, Latino leaders, checking in with Little Bangladesh, Thai, and others, asking, Are you okay? How are things in your community? Establishing those connections, maintaining them, building trust, and keeping the lines of communication open has been essential.

Second, we have built up connections between the city and the communities. We’ve had numerous initiatives and efforts to connect City Hall and city government with the communities as well as with the police. That enabled City leaders to come together productively with community leaders at the First AME Church last week.

Third, there’s been intense scrutiny of the LAPD and, as a result, significant policy and institutional changes have been made. I’ve witnessed the progression of some of these changes. Yet, driven by present circumstances, there is a further need for cultural change in officers’ perceptions of the community and how they police. The LAFD went through a culture change and was one of the first fire departments to take on discrimination and inequality head on within its own ranks and organization. Over 15 years ago, we changed a century-old ‘good ol’ boys club’ culture. It was an unbelievably difficult process for an organization to undergo.

It began with top leadership, which was committed to change and sent clear messaging of change throughout the organization. From there, we reviewed policies and procedures, to change how the department operates to be more equitable and non-discriminatory. We create processes that institutionalized equal and fair treatment. But the most vital element was: how do we change the way our firefighters think, our very culture? That comes through very intense on-going training. We went outside the department and brought in Human Relations Commission staff and embedded them within the department. We had them infused their training into all the various department training programs, in addition to their specific human relations training. In the fire department, we had to change the way our people thought about equality and not being discriminatory, to get everyone committed to treating each other with respect.

Ricky Bonilla / CC BY-SA

Changing a culture is not a one-time effort. Change doesn’t come just by delivering an order. It doesn’t come from hiring a consultant, getting some training, then checking off a box it’s done. Change must be a continuous commitment, because otherwise, once a training or one-time effort is over, people will fall back.

In the end, if we want to prevent this kind of unrest from recurring, we all understand the need to continue police reform. The second and most fundamental part we have to change is the underlying issue, which is inequality. We know the issues: we need to do more about employment; we need to do more about education; we need to do something about supporting the family structure and role models in the community. It’s easy to say those things, but it’s extremely hard to create solutions to address it all. These are unbelievably complex societal issues, but that’s the challenge we must undertake for the future of all our communities and generations to come.

Click below to listen to the full podcast interview between Nils Gilman and Emile Mack.

Emile was a post-Korean War orphan, adopted by a South-Central Los Angeles African American family. Though growing up amid gangs, he went on to UCLA. He joined the Los Angeles Fire Department (LAFD) and rose to Chief Deputy, second-in-command. He created the LAFD’s 20-year strategic master plan. As the “go to” person for challenging high-profile issues, his initiatives changed the LAFD’s culture that had been plagued by inequity, hostile work environments, and multi-million-dollar litigation. He chairs the Mixed Roots Foundation and serves on the executive board of the Biddy Mason Foundation, who raises awareness and funding for the adoption and foster care community, respectively.